*DISCLAIMER* This post originated with a coincidental connection between the two series of the title of this piece in one actor: Robert Forster, who plays Sheriff Henry Truman in Twin Peaks: The Return. He appears alongside Mia Farrow and Rock Hudson in the third episode of MST3K: The Return with the disaster film Avalanche! The synchronicity of his appearance in both shows planted a little seed of an idea. The following is a narrow, tight-rope walk a few inches above the ground. The reader can fall off at any moment and still be safe. A metaphorical sprained ankle is the most harm that could come to you.

First, a few provisional, expository passages on the theory of nostalgia at work in the entertainment industry, and the possible results of its effect on the human psyche:

In 1989, Cameron Crowe penned and directed Say Anything. At the beginning of the film, Ione Skye’s character Diane Court memorably proclaims in her valedictorian speech to her fellow despondent Class of ’88 (with the exception of Lloyd Dobler of course!)

Having taken a few courses at the university this year, I have

glimpsed our future, and all I can say is... go back.

Sure, Diane’s dad Jim is all laughs, but the line falls flat on everyone else. We might also sit in silence like those in the audience, confused and unsure about what she means. If not for a party to look forward to in the evening, we might become fidgety, uncomfortable, and mistake her advice as a suggestion to turn away from our present-facing-future, wandering back into a mire of child-like nostalgia with almost-adult bodies…Nevermind, party time!

If you were taken by her speech to “go back” inside your body, inside your psyche, there is an excellently comfy armchair with the brand name Nostalgia. A ghost of love haunts it, guarding access and relief, necessitating an homage from us to an old and well-known form. It wants a sacrifice of the two things worth more for their usefulness to our existence than anything else: time and attention. When we take a seat and sit back, this kindest haunting occurs in our thoughts and feelings: we return to better times. Ahhh…we are no longer reaching for comfort in our awkward bodies. We calm ourselves before that something-scary-and-new and like a late-night visit in a kitchen of worry, we nurse from a plastic teat of childhood milk.

Is this what she meant by going back? As Say Anything moves along, quick relief comes from “go back” when Diane Court’s speech passes and the narrative brings us to the party. However, throughout the party that night Lili Taylor’s character Corey Flood is strumming her sad and angry songs about the toxic dude Joe who “rapped” before Diane’s speech (and who later gives Lloyd woefully terrible and misogynistic advice). Corey states she is going to play all 65 songs of pain that she wrote about Joe, but not to go back and stay. She goes back to go through her grief and emerge she-knows-not-who (this is a Jungian reading, to be sure). She faces Joe when he approaches her alone in a side room and though scared of what comes next, she’s able to walk away from his sap-trap. Most of us forget Corey’s living example in word and song of Diane’s speech. We just remember that image of John Cusack holding up that boom box playing Peter Gabriel.

[To acknowledge my composite image of film and television above] Skye’s bit of dialogue as Diane is just as metaphorical as Matthew Fox’s character Jack Shepard from ABC’s LOST (2004-2010) when he crazily screams to Kate at the end of Season 3 that “We have to go back!” How is this different from an escape into nostalgic feeling and an avoidance of our present-facing-future? We can just as well lose the sense of ourselves at the gates of the future as in the ruins of the past. Whether we’re graduating from high school with unrealistic ideas about college and careers, or hopping planes day after day at the end of our rope waiting for the miracle to come, we can (if we’re lucky) be stopped by these experiences which we stumble over and have no place for in our lives. The lack of place, which is what is common in Diane’s speech and Jack’s desperation, is the arresting feeling that can imprison us in our wish for indulgent rests in Nostalgia’s armchair. Go back, but go back to go through – remember Corey’s songs, not “In Your Eyes.”

While the future is unwritten, LOST is exceptional in that it agitates the heart and the mind to turn reflexively away from the screen and to look in on our own lives (but perhaps not for every viewer, as its nostalgia holds true with new podcasts popping up devoted to re-watches and analyses even after close to a decade since its final episode). Like Jack, we can’t return to the same place to begin something new – we have to undergo some kind of journey. There is no new birth in nostalgia itself, as its inertia can keep one fixed like a mirage seeming to offer a familiar destination. Speaking to the human psyche as an individual, albeit a social individual, what could actually benefit one is a return to the paths and places-not-yet-set where we felt uncomfortable, where our nostalgia did not hold us in a Stockholm syndrome-like hug. It is possible to grow where time and attention are available to us without the crippling discomfort of the unknown. This is how we can find footing, and begin to progress beyond the state of the fool.

LET US NOW SLOW our narrative of the utilization of nostalgia and our challenge against it by focusing on two recent but very different shows that have promised to “take us back,” both using the subtitle or tag line “The Return”: Mystery Science Theater 3000 (MST3K) and Twin Peaks. The high contrast between these two television shows in form and in content is intentional, and can illustrate a number of things to us as audience members of streaming television in the early 21st century. Initial considerations are purely contextual:

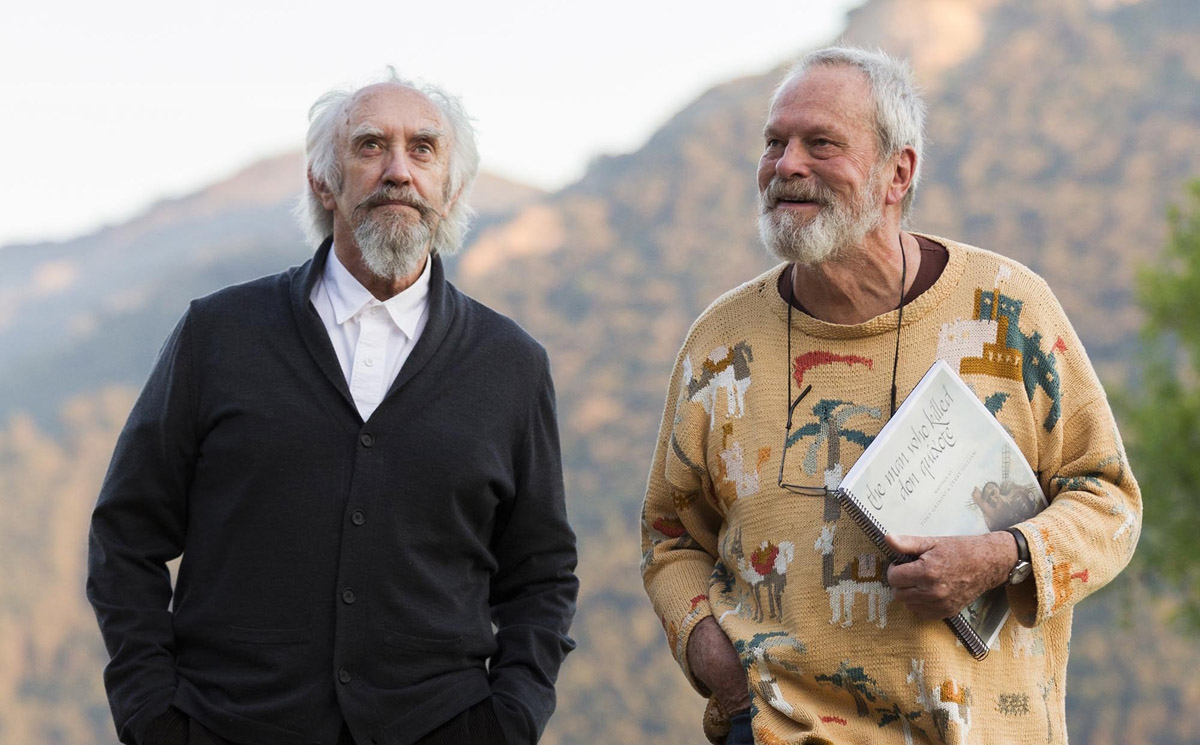

- Twin Peaks was brought back by Lynch and Frost following conversations in August 2012 between them and later in 2014 with exec Gary Levine, who was at ABC during the show’s original run, resulting in a drafting and developing of another season for Showtime; MST3K’s original creator Joel Hodgson secured funding for their return with a Kickstarter campaign (the most successful to-date for a TV/Film production at $5.7 million) after reacquiring the rights to the show with the help of Shout! Factory.

- Twin Peaks was released part-by-part in 18 weekly installments (with occasional breaks) by Showtime through multiple streaming services just as the first two seasons were classically aired on ABC; MST3K was dumped as a fully-watchable season on Netflix, as the streaming service and original content provider does so with all of their new shows.

- Lastly, just beyond the horizon of the contextual, Twin Peaks has been a highly influential sci-fi/mystery/horror show to the writers and producers of many subsequent productions, such as The X-Files, LOST, and scores of others; MST3K has had a different kind of cult influence – as a spoof on sci-fi and a riffing comedy that mocks and lampoons (with endearment) “the worst films ever made.” Indeed, Hodgson and Lynch/Frost couldn’t be more diametrically opposed, at least on conceptual and demonstrative grounds, as creators in the medium of television.

Despite these contrasts, both shows inspired and fed strong fan bases. Through the rallying of their support, each show was revived during their original runs to continue more episodes – in the case of MST3K on another network (the SciFi [now SyFy] channel) and for Twin Peaks a final number of episodes added to their second season on ABC. In this way, the idea that each are now “returning” is a wondrously nostalgic trick. These shows were brought back, and now it is happening again – the exact tagline of Twin Peaks: The Return. Each are returning with the creator’s own awareness that they are returning with all the accompanying fandom expectations and comparisons to their “original” forms. Each show navigates these treacherous waters in their own way with callbacks and references, continuations of plot threads, and bringing back characters who have disappeared long ago. In the case of Twin Peaks: The Return, even characters who have long since died (David Bowie’s Phillip Jeffries, Frank Silva’s BOB, Don S. Davis’s Major Briggs, and a few others) somehow make an appearance. Television is a dark magic.

There’s nothing really new in what I have to write here. The phenomenon of returns has fast become a trend in television in this second decade of the 21st-century and does not seem to be slowing down. It follows the same commercial trend of film sequels and re-boots that are regularly green lit in Hollywood. What differentiates both MST3K and Twin Peaks in their format is that each of these returns are intentionally limited in their release and their short burn is a trademark of how nostalgia, despite being so useful to gain our time and attention once more, is unsustainable over long periods. MST3K has quasi-challenged this statement with their second (shorter) return season called “The Gauntlet,” marking the 30th anniversary of the show’s debut on Thanksgiving Day in Minneapolis in 1988 – but David Lynch and Mark Frost have no intention of continuing Twin Peaks with another season. The fan base for the show has only a reading left for them of Frost’s publication Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier written from the perspective of the return season character Agent Tammy Preston. While this writer thinks it is a bookend worth checking out, some fans feel that this book and Frost’s previous The Secret History of Twin Peaks are non-canonical works from the series co-creator, you know, the-one-who-is-not-David Lynch.

LET US ADMIT that the demand to produce continual, original content, updated like software, is no guarantee of a quality experience because of re-investment in our nostalgic memories. Both return seasons are their own new shows, but viewers undoubtedly draw on their feelings and impressions of a past nostalgic experience with their predecessors – and compare. Audiences are mixed in their reactions but nonetheless these productions guarantee spent time and attention (and money earned). On the other side of the screen, the actors who are paid to be a part of the return can be less than enthusiastic to re-inhabit their past roles.

ANOTHER CASE in point, the two return seasons of The X-Files. Each sorely lacked the depth and vision of the original series, and are unarguably weak in their conception and demonstration of an earlier millennial (the time, not the generation) style and flavor. Interestingly, David Duchovny’s revival as Denise in Twin Peaks: The Return is full of life, but as Mulder he is a kind of Casper the Friendly Ghost – there-but-not-there – and the dramatic weight falls on Gillian Anderson and the supporting cast to carry any of what little coherence the writing has for them. Anderson’s character arc as Scully has been the focus of the show since the last few seasons (and arguably the films as well) and in the case of their return seasons, has portrayed Scully with care, maturity and skill. Unfortunately, Duchovny overburdens and isolates her dramatic force much too often with lethargic deliveries and detached affect. Combined with the weak writing, it’s a slough to get through. SPOILER ALERT not SPOILER ALERT: The Cigarette Smoking Man is still trying to pull all the strings and it’s just about as interesting as watching people recycle their glass and cans at a grocery store.

When it comes to MST3K‘s return, Joel Hodgson and his team of writers have the benefit of new characters and a new scenario that mirrors the first incarnation and plays with strange combinations and guest stars. It’s moderately amusing and there are some quality riffs and jokes. Twin Peaks however must (and I believe, does) deliver the relish of newness with the trick of a return, gifting us memorable new characters and in some cases the wondrous evolution of our old favorites. Lynch and Frost have been sensitive and highly aware of the expectations of the fan base’s secret wishes, and the use of the alternate-Coop and “Dougie” can be seen as the very reflection of the frustration to get back the Agent Cooper they left in a different kind of armchair at the Black Lodge. Like the finale of LOST, it has divided fans new and old – but much like anything truly worthy of our time and attention, we are left on the other side of the screen with the question “why?” – which we can choose to pursue, or not…

This writer feels he must pull back as far as he can and see the whole project of Twin Peaks: The Return in the round as a journey through the nostalgia of its own fandom, the mythology of the original show, as well as Lynch’s entire on-screen canon. The utilization of Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me as being integral to the substance of the story arch of The Return in particular is a brilliant move and so inimical to the desire for us to sit down in our armchair – almost as if like William Castle, Lynch and Frost have placed an electric buzzer there to go off whenever we find ourselves too comfortable in our assumptions about what is happening and how things are going to unfold with our beloved characters. In this, there’s a lesson for us to internalize, and for Hollywood and the streaming giants of Hulu, Amazon and Netflix to consider when they soon gift us with another project that promises to take us back.